Introduction

After our previous post, we are returning to the subject of modern-day communication - digital communication - where we are app users with a solution-conscious approach. The aim is to raise digital users’ awareness of issues relating to the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and privacy. Human beings communicate daily and increasingly (or perhaps almost exclusively) through the use of apps that exploit the Internet: some are exceptionally well-known and popular among users, such as Whatsapp, Signal, Telegram, Messenger, Skype, etc.

We know there has been a lot of debate in recent months, at least about the first three and which one would be best. We do not intend to carry out a technical analysis of the individual apps but to focus on specific aspects and offer food for thought. We hope that this contribution will help raise awareness among readers. Notably, on the one hand, we hope to raise awareness of people who use digital communication systems awareness to make a careful platform choice. On the other hand, we also hope to raise awareness of developers and platform providers in respecting users’ rights (‘data subjects’ in terms of personal data protection), paying attention to ethically oriented solutions. Therefore, the choice of communication system, which seems trivial at first, is not at all, and very often, decisions are made very quickly and precisely without awareness. A further premise is necessary: we do not intend to become solution providers, but simply to set out the primary considerations - some of which have emerged from concrete experiences - that should underlie an “informed” choice. We cannot ignore that it might verify cases of a real addiction to Whatsapp for users. An author perceived even the phenomenon almost like a domestication system of users to describe it in the article entitled WhatsApp and the domestication of users. In reality, beyond any exasperation that is never useful, we must avoid the risk of falling into a vortex of this kind that could lead to ‘addiction’ to a technological solution, almost as if it were an addict’s disease. There are several solutions to consider. One cannot justify oneself with “I can’t delete Whatsapp”; otherwise “I’ll be out”, or something else like “everyone communicates with Whatsapp and I can’t avoid it”. If these are the premises, what is our freedom (also, but above all, digital) in the communication context? What freedom to control one’s personal data? Below, therefore, we describe some of the criteria we have taken into account to define a broad assessment. The point, in essence, is limited to the choice of the app to be used for digital communication, placing itself critically on the issue.

Security: essential but not the decisive criterion

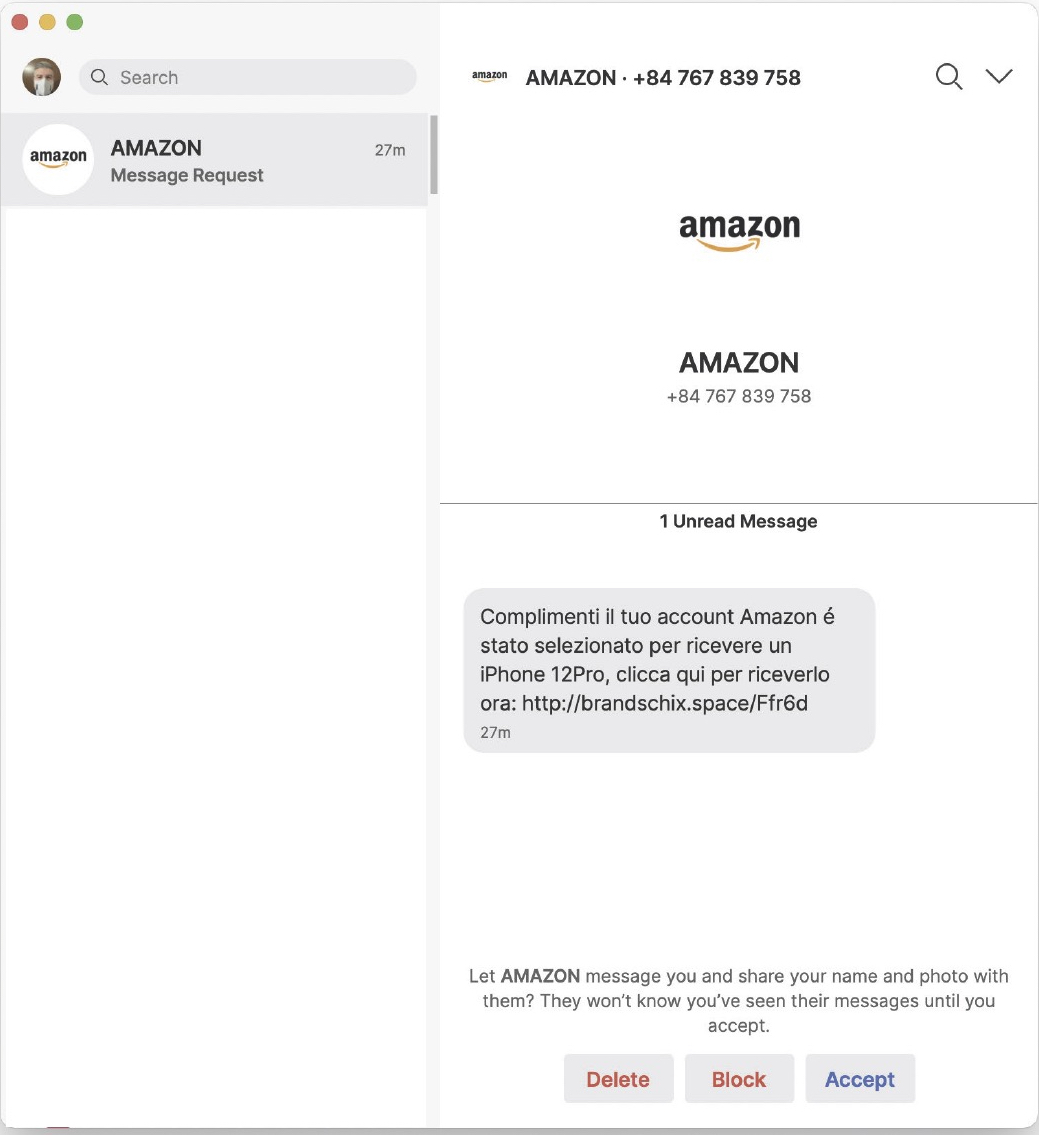

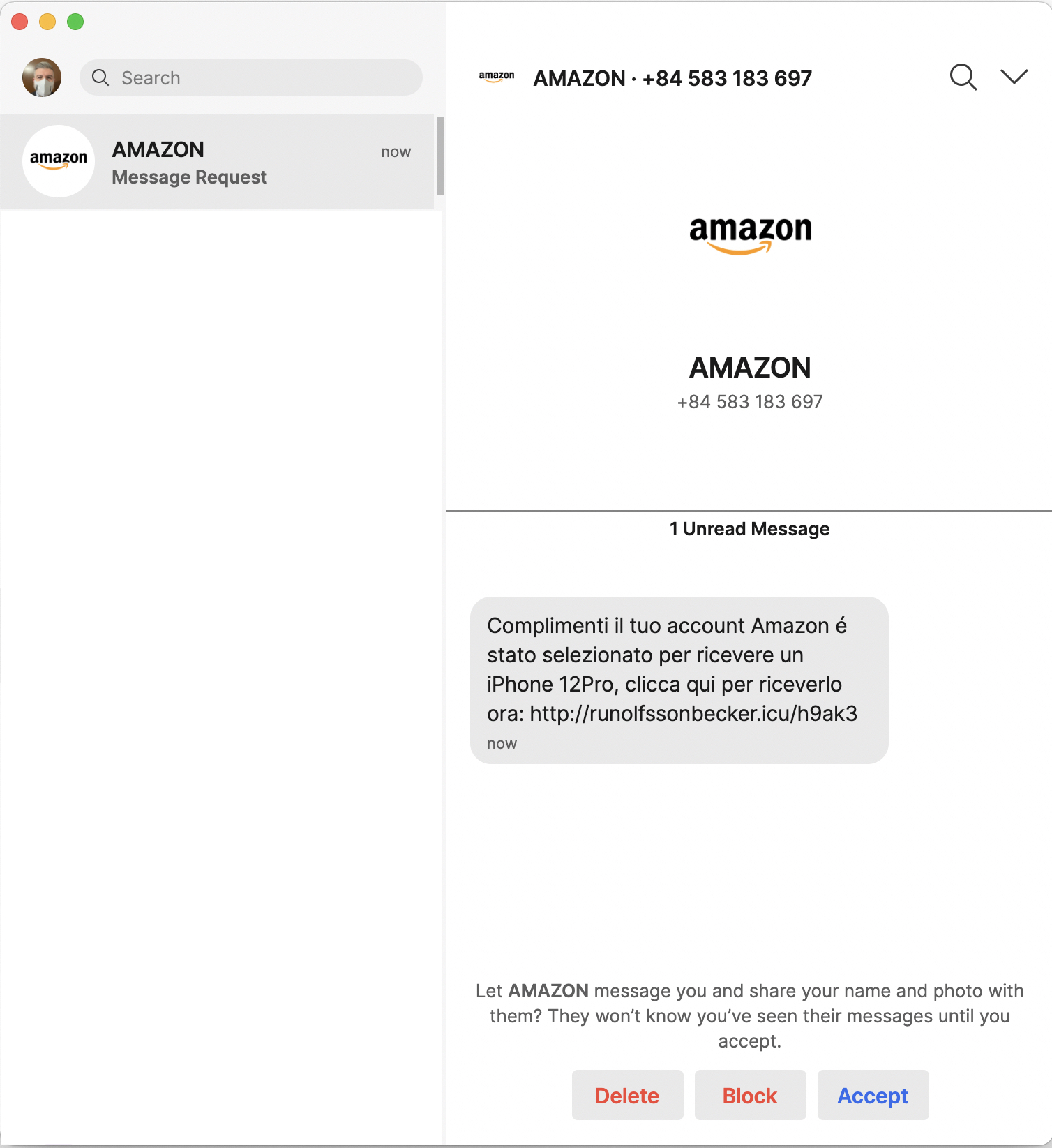

The main question from users seems to be: “Is the app secure?”, or rather: “What is the most secure app?”. The question is wrongly posed because security (so to speak, but we need to understand what is meant more precisely) is not the (only) criterion for making the right choice. If the question on the security were whether developers have encrypted messages, the answer would be yes, at least for Whatsapp, Signal, Messenger and Skype. Telegram uses the MTProto 2.0 protocol with end-to-end encryption (E2EE) for Secret Chat and Voice Calls. Signal and Whatsapp - based on a partnership dating back to 18/11/2014 - use the same E2E encryption protocol developed by Open Whisper Systems. Those who expected Signal to use a more effective encryption protocol than Whatsapp were probably disappointed, not least because they ‘discovered’ the partnership a few years ago. However, security should not be considered solely about message content and delivery to the recipient.We do not focus on attacks on the provider’s infrastructure, as they should take appropriate measures. However, there may also be risks from attacks on individual users, such as phishing attempts. Here are two pictures of phishing attempts on Signal that occurred a few days apart.

The human factor could be the weak link if the user has a positive reaction to such messages. At this point, you have to wonder if these kinds of attacks can be prevented on specific platforms or solutions. Probably not. We believe, therefore, that security is not the determining element for the choice that users should make. Undoubtedly, it is one of the requirements - moreover, required by the legislation on the protection of personal data (GDPR) both concerning the security of the processing (art. 32) and about the principle “Data Protection by design and by default” (art. 25) - but it is not the diriment one. Thus, the user is guaranteed confidentiality, integrity and availability of data. At this point – met the security requirement - we can award a point favouring both the user and the provider.

Open-source: not an insignificant criterion but may prove illusory

Once it has been pointed out that security is not in itself the fundamental criterion and that the user is in any case guaranteed, it should be understood whether the algorithm is open-source or not. In some cases (Telegram), only the clients’ source code (the apps developed to use the platform) is open source, but not the server-side source code. The advantage of open-source code (e.g. Signal) is that it allows one to know how the algorithm processes instructions. Indeed, it is undoubtedly an indication of transparency since the developer claims to enable the algorithm code analysis. The subject of open-source software is also the subject of a philosophical approach known by the term FLOSS, which stands for Free, Libre, and Open-Source Software. Sometimes one also finds the other expression FOSS, which stands for Free and Open Source Software; for the differences between the two terms, we refer to Richard Stallman’s contribution. On the contrary, the Whatsapp user would not code the algorithm and, thus, the relevant processes. Returning to the more practical aspects and, therefore, to the better-known solutions, Signal has open-source code, whereas Whatsapp does not. From the user’s point of view, how important is the open-source criterion in the choice? Should the user consciously opt for an open-source solution (Signal) or go for a proprietary algorithm (Whatsapp)? Transparency is always appreciable because it does not obscure anything but rather provides excellent clarity. Some, however, might invoke the ’trust’ element to justify the choice of an app with proprietary (and therefore not open) code simply because they trust the provider. Considering that the focus is on protecting the data subject’s personal data, one would expect an informed user to choose an open-source code app. Indeed, beyond the existing legislation on personal data protection, this is more in line with the principle expressed in Whereas (7) of the GDPR, where we read: “Natural persons should have control of their own personal data. Legal and practical certainty for natural persons, economic operators and public authorities should be enhanced”.

Therefore, the issue of control of one’s personal data is primary and would be decisive in guiding an informed choice aimed solely at deciding whether the solution (in this case, Signal) offers guarantees to the data subject in compliance with the applicable data protection regulations. Otherwise, the data subject should not reasonably consider such a solution. However, the open-source source code might be an illusory aspect when the same code is any way in the exclusive availability of a party (provider) because the system’s architecture is centralised (e.g. Signal). But we will return to the issue of the centralised system shortly. At this point, we get from the open-source code a point in favour of both the user and the provider.

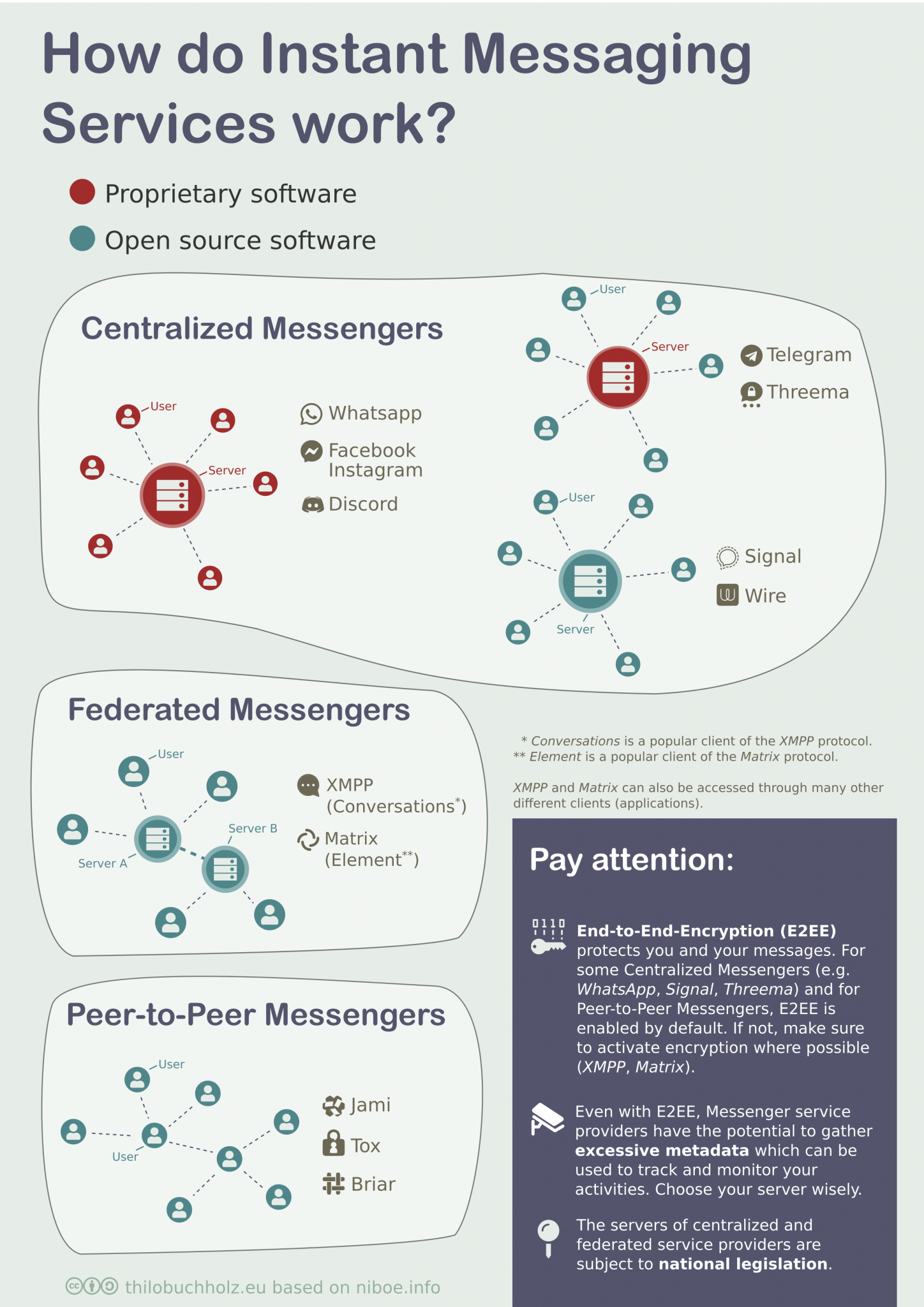

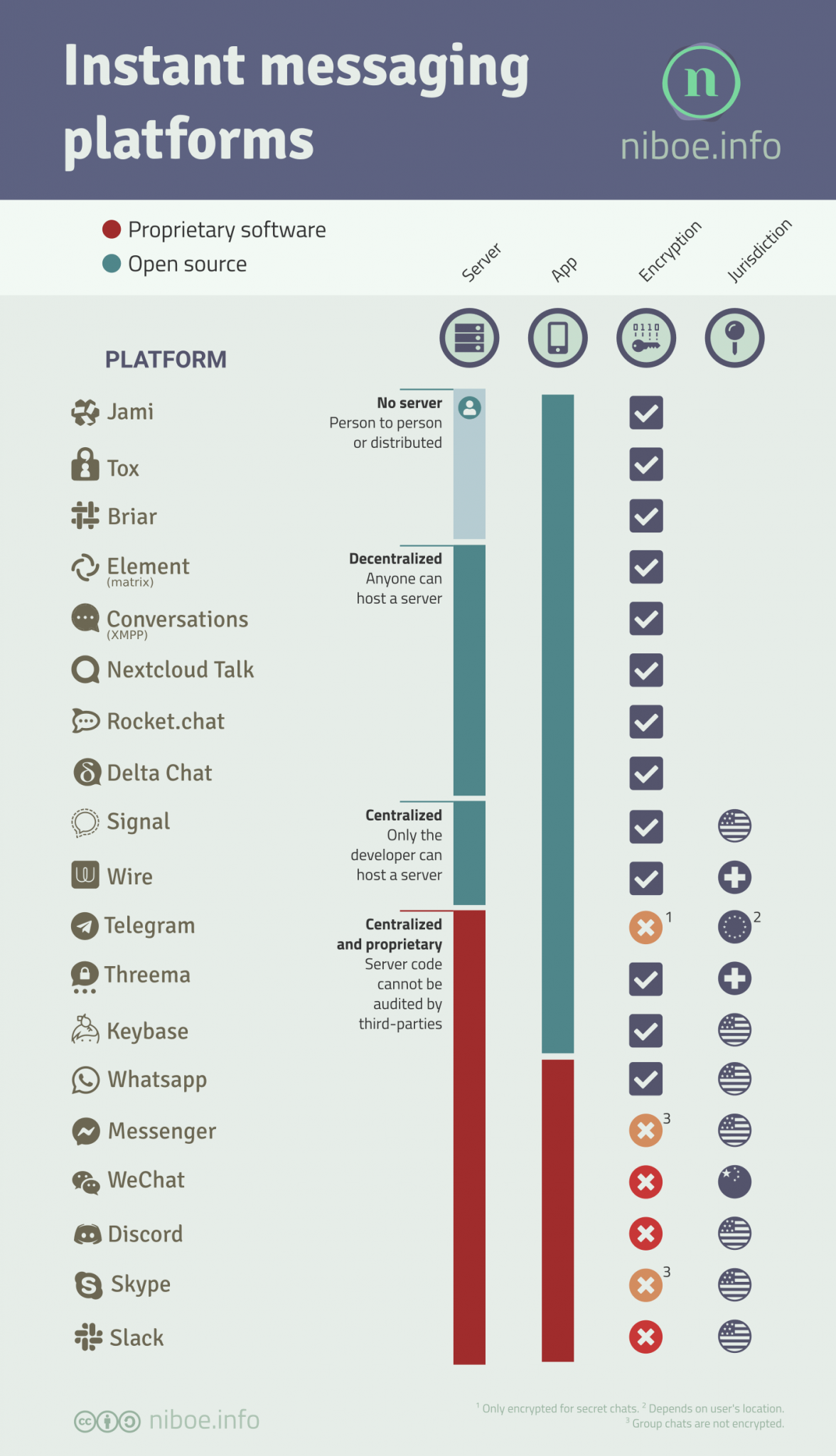

Different systems: centralised, federated, distributed or decentralised

Another aspect concerns the choice of system architecture: centralised, federated, distributed or decentralised. We find a concise but compelling description in the following two infographics created by Thilo Buchholz.

|

|---|

| Credits Thilo Buchholz |

|

|---|

| Credits Thilo Buchholz |

The images are in themselves extraordinarily eloquent and need no further comment.

Federated systems: XMPP and Matrix

In a previous contribution to which we refer, we summarised the XMPP protocol, by which it possible to create a federated system. The origins of the XMPP protocol date back to the end of the 1990s and communication is based on servers with open-source software federated with each other1. Apart from the technical aspects, it is interesting to note that the XMPP protocol has been used for some well-known apps (Google Talk, AIM, Facebook Chat) and is protocol-based for other equally well-known ones (Whatsapp, Zoom, Jitsi). The point is that some major players have decided to close (’the boxing of XMPP’) the XMPP protocol in proprietary code, to the disappointment of open-source developers. Another example of a federated system is the Matrix project: it is a complex project and more extensive than those that simply use the XMPP protocol.

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction is another element to consider. The current legal and regulatory situation regarding the transfer of personal data between Europe and other countries is well known. Following the judgment of the Court of Justice of the EU of 16/7/2020 in Case C-311/18 (known as Schrems II), the transfer of personal data to third countries is permitted on condition that an adequate level of protection of the personal data transferred is guaranteed, ensuring to grant data subjects effective and enforceable rights and effective administrative and judicial remedies. Given this, a European citizen should prefer a data controller whose service is within the Union. However, the jurisdiction profile also affects any country’s institutional bodies’ requests to whose jurisdiction the provider belongs. Indeed, a provider located in the US could receive requests from the US Government or US law enforcement. What protection for the data subject? Given these relevant aspects, the most suitable solutions are those that use the e-mail address (DeltaChat), the XMPP protocol or federated systems that lead back to the device of the person concerned.

Internal or endogenous digital sovereignty - self-sovereignty

We should not underestimate the role and relative positioning in the international context, including the specific providers’ market. We often hear talk of digital sovereignty referring to the State as an expression of the power attributed to the State in the sphere concerning any activity classified as ‘digital’, i.e. linked to or derived from the use of technologies. However, we believe that “digital sovereignty” is not exclusively identified with the State’s power. Indeed, we think that “digital sovereignty” can also express the models adopted by private actors to exercise (in autonomy and with complete control) power over their digital domain. We refer to both the actions they can take and the choices of particular technologies adopted for their activity. Thus, any activity by which to guarantee their digital heritage. To sum up, each of the providers, such as Google, Facebook, Whatsapp, Signal, etc., expresses internal digital sovereignty since it consists of power over its digital domain. However, this internal (endogenous) digital sovereignty is expressed externally through the proposition of services and positioning in the market. Therefore, each of the major players providing digital services, expresses digital sovereignty related to its sector, consisting of having complete control over the offered products, even for free. In essence, Whatsapp, with its app, although free of charge, exercises its digital sovereignty to affect the market. The same applies to other actors such as Signal, Telegram, Facebook, Instagram, etc. On this point, we refer to our contribution entitled “Digital sovereignty between ‘accountability’ and the value of personal data”. Why do we refer to digital sovereignty? The reason is always related to a reading with a focus on data protection. The existence of digital sovereignty in the hands of a private entity, if it does not guarantee the data subject complete control over his or her personal data, is not compatible - even partially - with data protection legislation. This scenario could also have an essential ethical consequence. Important players that provide - also free of charge - messaging services (e.g. Whatsapp) declare in their privacy policies and terms of service that they comply with current legislation on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data. What “control” do individuals have over their personal data (Whereas (7) of the GDPR)? The “control” would take the form - before use - of accepting or not accepting the conditions of service and - after use - of exercising the rights indicated by the GDPR (for European citizens), possibly requesting cancellation. We consider that the meaning of the expression “Natural persons should have control of their own personal data“cannot be interpreted in such a reductive way.

Technology neutrality: aiming for another goal

We have deliberately referred to some technical aspects in our reflections, albeit of a general nature, only to describe solutions and not explore areas reserved (probably but not exclusively) for developers. In any case, we believe that an in-depth study of the more technical aspects could help broaden knowledge. As far as the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data is concerned, technology is neutral. Indeed, legal rules do not indicate the technology to use since it is the achievement of the effect shown in the rule that is important and not the means (which must be lawful) used. Therefore, we mean that there is no legal obligation to choose a specific technology, free to choose the most effective one to comply with the current legislation. Therefore, the user will have to be concerned that his or her personal data will be processed by the data controller in compliance with the rules on security of processing, the principles of data protection by design and by default, and any other relevant provisions. According to the provider’s statement, the data subject’s choice of the app should be oriented towards solutions that guarantee, according to the provider’s information, these regulatory compliances instead of the fulfilment of other motivations, respectable but with less legal merit. The developer, the developer, does not exempt the provider from the obligation to be clear in the app’s description, especially regarding how secure it is but to compliance with data protection regulations.

Ethics and control of personal data

Last but not least, ethics are often not taken into account at all. We believe that ethics concerns everyone and - in this case - both the person concerned and the provider. As a user of the app, the data subject should make an ethically oriented choice towards the app with which he or she will communicate with others and not an indiscriminate one. On the other hand, the developer will also have to take care of an ethical approach in the development and production phase. In essence, the reference to ethics must always be present from the design phase to the production phase, just as if one had to respect the principle of “data protection by design and by default” (art. 25 GDPR) or, for the rest of the world, the very well-known principle of “Privacy by Design”.

Conclusions: the final choice

At this point, before presenting our conclusions, it is necessary to point out that we conduct our investigation using the DAPPREMO (Data Protection and Privacy Relationships Model) approach, to which we refer for further details. While thanking the reader for the patience of having continued reading so far, we express our personal assessment of current messaging solutions at the end of this reflection. We believe that there is no such thing as the absolute best technical solution, but instead developed and enabled by the relevant regulations. We have to clarify that what we describe is not an endorsement but the result of our evaluations following “field tests”. Our choices are therefore directed towards federated or distributed systems since they appear to be better geared towards compliance with the rules on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data. In particular, these solutions appear to be suitable for guaranteeing individuals control over their personal data, as provided in Whereas (7) of the GDPR. Undoubtedly for communication, you can use a secure and robust email service such as ProtonMail or, for whom you prefer, a self-hosted service, Mailcow. For messaging, we suggest evaluating:

- DeltaChat

- systems with XMPP protocol

- Matrix / Element

- Tox (After some tests, we seem that there are some bugs: problems exchanging messages, difficulties in synchronization between different devices, contact search. We hope that the developers can intervene in the project).

If you are interested in deepening comparing other solutions, you can find further details on the website Privacytools.io, a relevant resource.

See the infographic above ↩︎